Variance Reduction

Charlotte Wickham

Oct 4th 2018

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE)

library(tidyverse)## ── Attaching packages ───────────────────────── tidyverse 1.2.1 ──## ✔ ggplot2 3.0.0 ✔ purrr 0.2.5

## ✔ tibble 1.4.2 ✔ dplyr 0.7.5

## ✔ tidyr 0.8.1 ✔ stringr 1.3.1

## ✔ readr 1.1.1 ✔ forcats 0.3.0## ── Conflicts ──────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

## ✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

## ✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()set.seed(101991)Finish last times slides

What about empirical comparisons of variance?

When our parameter of interest can be written as an expectation, we can use the CLT to guide us in quantifying the variance in our estimate.

But sometimes this might not be enough if:

- We aren’t convinced the CLT has kicked in

- We aren’t in a situation where the CLT applies (we aren’t using a sample average)

We could use simulation to estimate it…

Simulating to find the variance of a simulation estimate

One estimate of the required expectation:

num_sims <- 1000

many_sequences <- rerun(num_sims,

rbinom(20, size = 1, prob = 0.5))

longest_runs <- map_dbl(many_sequences,

~ max(rle(.)$lengths))

mean(longest_runs)## [1] 4.657Another…

many_sequences <- rerun(num_sims,

rbinom(20, size = 1, prob = 0.5))

longest_runs <- map_dbl(many_sequences,

~ max(rle(.)$lengths))

mean(longest_runs)## [1] 4.662But…really we want to automate this.

Take the same approach

- Simulate: repeat the prior simulation many times, each time getting an estimate of the desired expectation:

mean(longest_runs) - Calculate: nothing extra to do (

flatten_dbl()) - Summarize: sample variance of estimated expectations

The first step is now simulating a complicated thing, so wrap it up into a function:

mc_estimate_run_length <- function(num_sims){

# estimate the expected maximum run of H or T

# in 20 coin flips by monte carlo

many_sequences <- rerun(num_sims,

rbinom(20, size = 1, prob = 0.5))

longest_runs <- map_dbl(many_sequences,

~ max(rle(.)$lengths))

mean(longest_runs)

}

mc_estimate_run_length(1000)## [1] 4.608many_estimates <- rerun(500, mc_estimate_run_length(num_sims = 1000))

many_estimates_flat <- many_estimates %>% flatten_dbl()

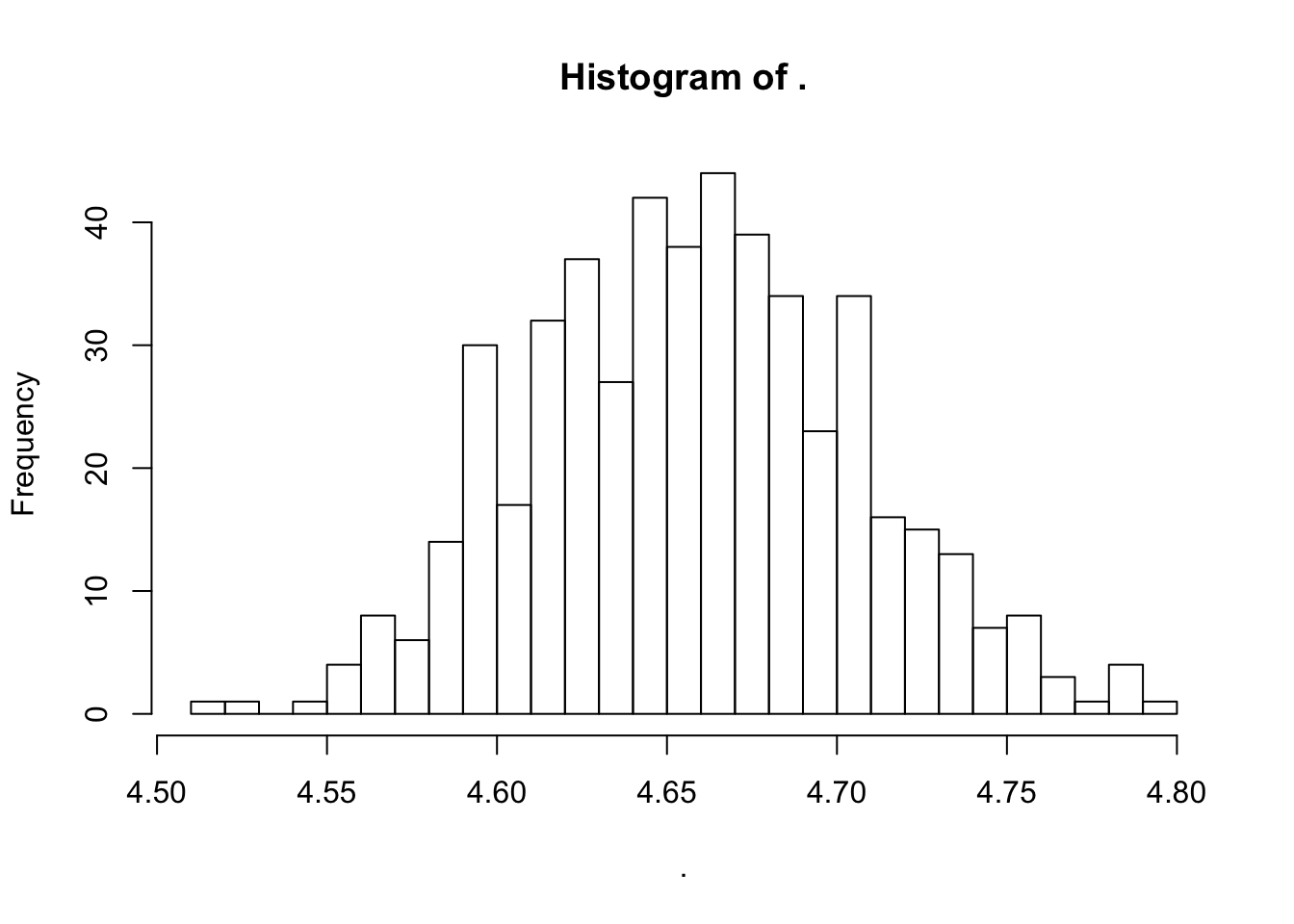

many_estimates_flat %>% hist(breaks = 20)

sd(many_estimates_flat)## [1] 0.04846478sd(longest_runs)/sqrt(1000)## [1] 0.04835384Compares well to our estimate that relied on the CLT (it should, the CLT should be pretty good for \(n = 1000\))

many_estimates %>% flatten_dbl() %>% sd(na.rm = TRUE) ## [1] 0.04846478sd(flatten_dbl(many_estimates), na.rm = TRUE)## [1] 0.04846478Your turn

Estimate the standard deviation of our MC based estimate, when we simulate just 250 coin toss sequences in each simulation.

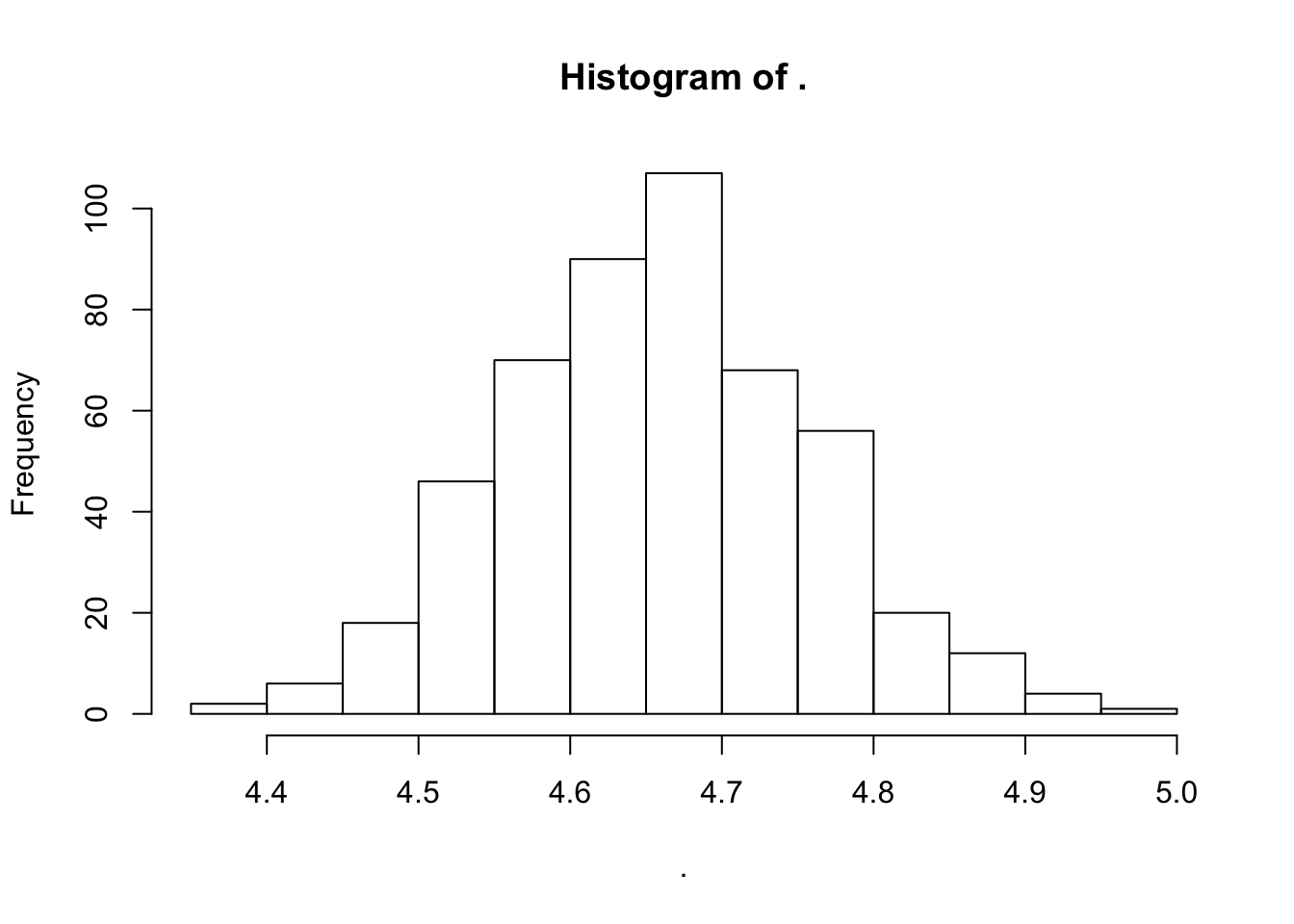

many_estimates <- rerun(500, mc_estimate_run_length(num_sims = 250))

many_estimates_flat <- many_estimates %>% flatten_dbl()

many_estimates_flat %>% hist(breaks = 20)

sd(many_estimates_flat)## [1] 0.09933127Does you answer agree with what the CLT might predict?

Back at 8:55am

Careful with \(n\)

Lot’s of sample sizes floating around:

- 500 the number of simulations we use to estimate the variance

- 1000 the number of simulations of coin toss sequences in each estimate of the expectation

- 20 the number of coins flipped

(that’s 10 million coin flips total)

Variance Reduction

An collection of techniques designed to decrease the variance of our simulation based estimate.

I.e. we can get just as good an estimate with many fewer simulations.

- Antithetic variables

- Importance sampling

- Common random numbers

- Control variates

- Stratified sampling

Antithetic variables

Setting:

We want to estimate: \[ \theta = \text{E}\left( h(X)\right) \]

We do this by:

Sampling \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) i.i.d from distribution \(F_X\).

Calculating \(h(X_1), \ldots, h(X_n)\).

Finding the sample mean of the \(h(X_i)\), i.e. \[ \hat{\theta} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i = 1}^n h(X_i) \]

Idea:

Instead of generating \(X_i\) independently, generate them in pairs, use the sample average of the pair averages.

Intuition:

The average of a pair of simulated values, \[ \text{Var} \left(\frac{1}{2} \left(X_1 + X_2\right) \right)= \frac{1}{4} \left( \text{Var}(X_1) + \text{Var}(X_2) + 2 \text{Cov}(X_1, X_2) \right) \] will be smaller than the average of two independently simulated values, if \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) are negatively correlated, i.e. \(\text{Cov}(X_1, X_2) < 0\).

But really…

We actually we are interested in: \[ \text{Var}\left(\frac{1}{2} \left(h(X_1) + h(X_2)\right) \right ) \]

It can be shown if \(h\) is monotonic that above relationship still holds: this variance will be less than the average of two independently simulated values, as long as \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) are negatively correlated.

An example

Let \(X \sim\) Uniform(0, 1). What is \(\text{E}\left(e^x\right)\)?

(We could answer this with calculus quite easily…but it’s a nice example to work with)

The naive MC approach:

n_sims <- 500

many_x <- runif(n_sims)

exp_many_x <- exp(many_x)

mean(exp_many_x) # our estimate of E(e^x)## [1] 1.731394# rough CI half-width on this estimate

(naive_ci_halfwidth <- 1.96*sd(exp_many_x)/sqrt(n_sims))## [1] 0.04364225(Don’t need rerun() here, it’s easy to get many samples from a Uniform)

The antithetic variable approach

\(h(X) = e^x\) is monotone in \(x\).

So, we should be able to reduce variance by generating pairs of negatively correlated draws from a Uniform(0, 1).

One set of pairs: \((X, 1-X)\) where \(X \sim\) Uniform(0, 1)

Both \(X\) and \(1-X\) have the right distribution and are negatively correlated.

x_first_in_pair <- runif(n_sims/2) # need half as many draws

x_second_in_pair <- 1 - x_first_in_pair

# a useful function in this example

pair_average <- function(x1, x2){

1/2 * (x1 + x2)

}

pair_averages <- pair_average(x1 = exp(x_first_in_pair),

x2 = exp(x_second_in_pair))

mean(pair_averages) # our estimate of E(e^x)## [1] 1.719627# rough CI half-width on this estimate

(antithetic_ci_half_width <- 1.96*sd(pair_averages)/sqrt(n_sims/2))## [1] 0.0081728985 times smaller!

Antithetic variables takeaways

- Need to be in a setting where the \(\text{E}(h(X))\) is of interest

- \(h(x)\) needs to be monotone

- Can get big variance reductions

- You might only need to sample half as many points

Next week reading

Wilson G, Bryan J, Cranston K, Kitzes J, Nederbragt L, et al. (2017) Good enough practices in scientific computing. PLOS Computational Biology 13(6): e1005510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005510

a minimum set of tools and techniques that we believe every researcher can and should consider adopting.

Read the Author summary, Overview, Introduction and Software sections.

You may also want to review some things we touched on in class about functions in R: