Random Numbers

Charlotte Wickham

Sep 25th 2018

Preliminaries

Syllabus

What questions do you have?

Prior R survey

Experience with R:

| comfortable | copy/edit | never used |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 10 | 1 |

Experience with tools/functions/packages

| tool | never used it | not comfortable | comfortable |

|---|---|---|---|

| rmarkdown | 4 | 5 | 11 |

for |

5 | 5 | 10 |

apply() |

6 | 7 | 7 |

| git | 11 | 7 | 2 |

Predict the output

x <- c(1, 2, 3, 4)

y <- c(0, 1)

z <- c("a", "b", "c", "d")| Code | Percent Correct | Correct Answer |

|---|---|---|

z[2] |

100 | "b" |

x <- y; x |

90 | 0 1 |

x < 4 |

90 | TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE |

z[x<2] |

65 | "a" |

x + y |

30 | 1 3 3 5 |

z[-2] |

30 | "a" "c" "d" |

Getting help

Office hours:

- Tue 11-11:50am 255 Weniger (Charlotte)

- Wed 3-3:50pm TBA (Sam)

- Thu 11-11:50am 255 Weniger (Charlotte)

Open an Issue in the Discussion Repo…more in lab/homework

Simulation

Simulation is a way to explore the properties of a random variable, e.g.:

- Particularly hard to analyse processes

- Properties of an estimator/test in scenarios it wasn’t designed for

- A method for conducting a hypothesis test

But, we have to be able to simulate a random variable!

This week: methods for simulating random variables.

Next week: what can you do with those simulations…

General idea

If we could simulate a Uniform(0, 1) there are methods we can use to get other distributions.

Today:

How to simulate from a Uniform(0, 1).

One way to use a Uniform(0, 1) to simulate from another distribution: inverse transform method

What makes code “good”?

Aside: Workflow

Sometimes (like last Thursday), I’ll provide an entire project for our work in lecture. You will log in to rstudio.cloud, find it and copy it.

Sometimes, I’ll just work from the lecture notes:

- You’ll want the RMarkdown document - linked on website

- Either open and work on your copy of RStudio, or use cloud.

I’ll always re-Knit (with results included), and re-post the lecture after class.

Psuedo-random numbers

In R runif() produces random draws from a Uniform(0, 1) distribution, and relies on a pseudo-random number generator.

runif(n = 10)## [1] 0.2338991 0.9260319 0.2718123 0.5667901 0.2671424 0.6279740 0.4020896

## [8] 0.4183823 0.6643049 0.2313253The first argument n controls how many numbers are drawn.

Your Turn (2 mins)

You read about one pseudo-random number generator, the Multiplicative congruential method.

(runif() uses a more complicated generator, but the principle is the same.)

- Why is the method known as pseudo-random?

It’s a deterministic algorithm.

It’s recursive, uses a seed (first number), it’s cyclic (numbers will eventually repeat). Seed, based on the time now?

- Will you get the same sequence I did? Why, or why not?

No. We don’t have the same seed. (But assuming we are all using the same R version the default generator and its parameters will be the same.)

Try it:

runif(n = 10)## [1] 0.7573553 0.4453555 0.6937774 0.3896192 0.2322473 0.2652118 0.7575507

## [8] 0.4705431 0.4004783 0.7948263Seeds

The seed is the first number used to start the generating sequence (\(x_0\) in the reading).

Two ways to get a seed:

Create an unpredictable one when needed:

Initially, there is no seed; a new one is created from the current time and the process ID when one is required. Hence different sessions will give different simulation results, by default.

– from

?RandomSet a specific one to ensure the same sequence. Good for: debugging, comparing to someone else, removing sampling variability. In R:

set.seed(seed), whereseedis some integer.

Your Turn (2 mins)

Will the code in these two chunks give the same 20 random numbers? Guess, then try it.

set.seed(1871)

x <- runif(10)

y <- runif(10)

(unif_1 <- c(x, y))## [1] 0.44482382 0.46826211 0.11013158 0.33573747 0.31285982 0.15742834

## [7] 0.90300484 0.59244524 0.47035439 0.50336048 0.99857384 0.84269130

## [13] 0.22613531 0.06823719 0.92291775 0.35295546 0.24142579 0.33392353

## [19] 0.56343514 0.50514421set.seed(1871)

(unif_2 <- runif(20))## [1] 0.44482382 0.46826211 0.11013158 0.33573747 0.31285982 0.15742834

## [7] 0.90300484 0.59244524 0.47035439 0.50336048 0.99857384 0.84269130

## [13] 0.22613531 0.06823719 0.92291775 0.35295546 0.24142579 0.33392353

## [19] 0.56343514 0.50514421(How could we check with code?)

all(unif_1 == unif_2) # OK here, dangerous in general because of floating point error## [1] TRUEall.equal(unif_1, unif_2) # Gives more info if not TRUE## [1] TRUETake-aways

Most programming languages use a deterministic process to get numbers that appear random.

These sequences depend on an initial state, known as a seed. If you start from the same seed (with the same generator) you will get exactly the same sequence of random numbers.

R keeps track of the state of the sequence for you. You can set the seed with

set.seed()if you want the sequence to be reproducible.

Unanswered questions:

- What generator does R actually use? See

?Random. How does it work? - How are pseudo-random number generators evaluated? I.e. what makes a good pseudo-random number generator?

Inverse Transform Method

@8:36am

A method for generating a sample from a stated distribution, by using a sample from a Uniform(0, 1).

Relies on inverting the cumulative distribution function.

So, you need to have a form for the CDF and be able to invert it.

Intuition

To generate a sample, \(X\), with cumulative distribution function (cdf) \(F(x)\):

- Sample \(U\) from a Uniform(0, 1)

- Calculate \(X = F^{-1}(U)\)

Add sketch here

We are generating a quantile at random, and using the inverse CDF to translate the quantile back to the support of the CDF.

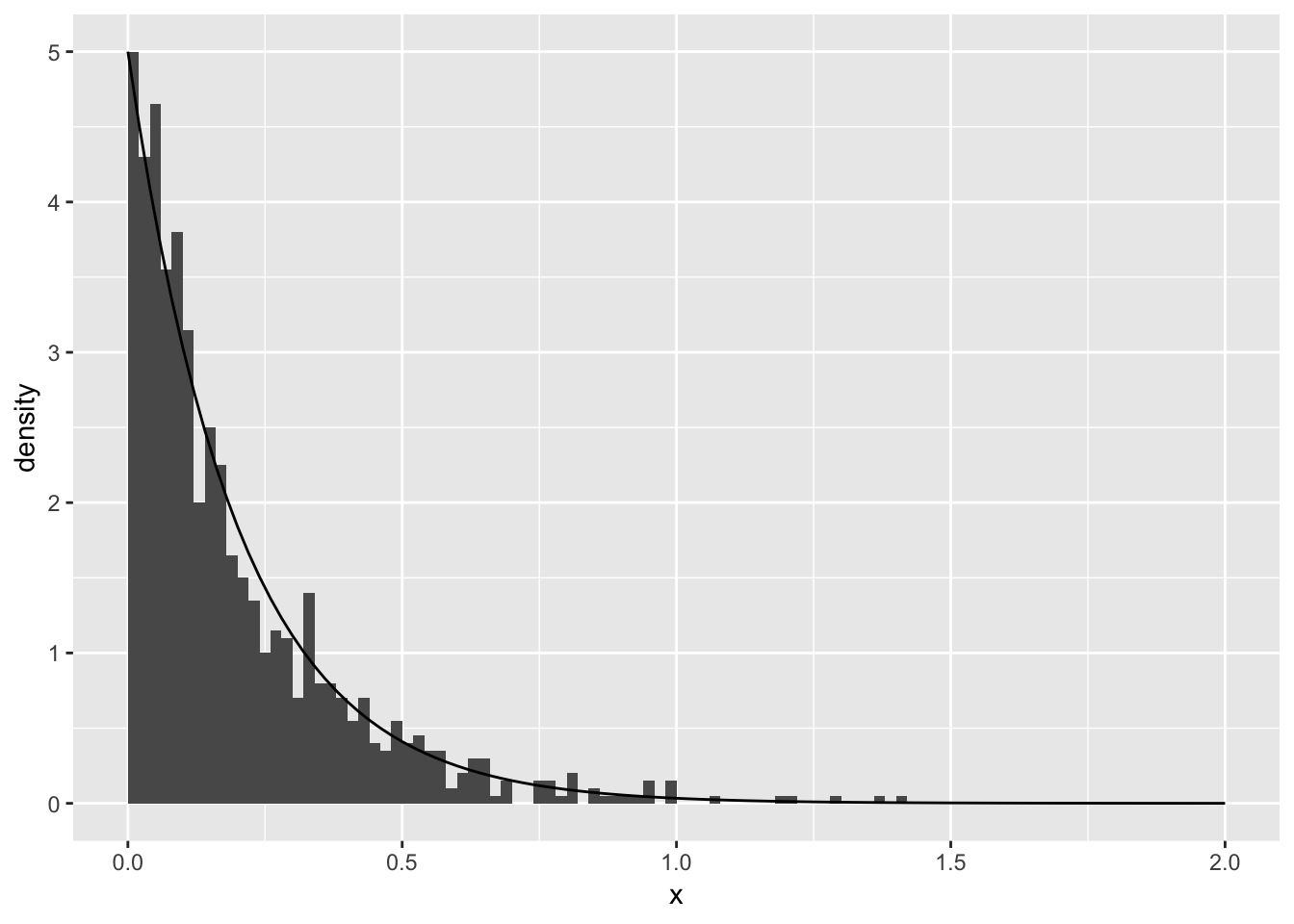

Continuous case - Exponential

Goal: Draw a sample from Exponential(\(\lambda\)).

If \(X \sim Exp(\lambda)\), \[ F(x) = 1- e^{-\lambda x} \]

Invert the CDF, let \(x = F^{-1}(u)\) \[ u = 1 - e^{-\lambda x} \\ (1 - u) = e^{-\lambda x} \\ \log(1-u) = -\lambda x \\ F^{-1}(u) = x = -\frac{1}{\lambda} \log(1-u) \]

Continuous case - Exponential

To simulate \(X \sim Exp(\lambda)\):

- Generate \(U\) from Uniform(0, 1)

- Set \(X = -\frac{1}{\lambda} \log(1-U)\)

u <- runif(1)

lambda <- 5

(x <- -1 / lambda * log(1 - u))## [1] 0.03831972How can we check this is working?

Generate many and plot.

Your turn

Edit to generate 1000 samples from Exponential(\(\lambda\)):

u <- runif(n = 1000)

lambda <- 5

x <- -1 / lambda * log(1 - u)library(ggplot2)

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = x)) +

geom_histogram(aes(y = stat(density)),

binwidth = 0.02, center = 0.01) +

stat_function(fun = dexp, args = list(rate = lambda)) +

xlim(0, 2)

Discrete case - Bernoulli

(back at 9:01am)

\[ \begin{aligned} P(X = 1) &= \pi \\ P(X = 0) &= 1 - \pi \end{aligned} \]

Application of the inverse CDF method, to simulate \(X\):

- Generate \(U\) from Uniform(0, 1)

- If \(U < \pi\), set \(X = 1\), else set \(X = 0\).

(See Ross 4.1 for more details)

Game plan: three different implementations, compare and contrast.

Implementation #1

A literal translation:

pi <- 0.4

(u <- runif(1))## [1] 0.4196467if(u < pi){

x <- 1

} else {

x <- 0

}

x## [1] 0Can you edit to sample 1000 numbers from Bernoulli(0.4)?

No, the condition inside if() is interpreted as a length 1 logical:

pi <- 0.4

u <- runif(1000) # this doesn't work

if(u < pi){

x <- 1

} else {

x <- 0

}## Warning in if (u < pi) {: the condition has length > 1 and only the first

## element will be usedx## [1] 0Implemention #2 - Your turn

Use subsetting instead:

- Set

xto be 0 - Where

uis less thanpi, setxto 1.

pi <- 0.4

u <- runif(1000)

x <- double(1000)

x[u < pi] <- 1Can you edit to sample 1000 numbers from Bernoulli(0.4)?

Pick up here Thursday

Implementation #2.5

?ifelse

ifelsereturns a value with the same shape astestwhich is filled with elements selected from eitheryesornodepending on whether the element oftestisTRUEorFALSE.

u <- runif(1000)

pi <- 0.4

x <- ifelse(u < pi, 1, 0)Implementation #3

Use built in function:

pi <- 0.4

x <- rbinom(n = 1000, size = 1, prob = pi)Your Turn

We have a few implementations:

# 1

if(u < pi){

x <- 1

} else {

x <- 0

}

x# 2

x <- 0

x[u < pi] <- 1# 2.5

x <- ifelse(u < pi, 1, 0)# 3

x <- rbinom(n = 1000, size = 1, prob = pi)# 4 an addition

x <- 1

x[u < pi] <- 0# 5 a student solution

as.numeric(u < pi)How do we judge which code is best? What are the advantages/disadvantages of each implementation?

What makes code good?